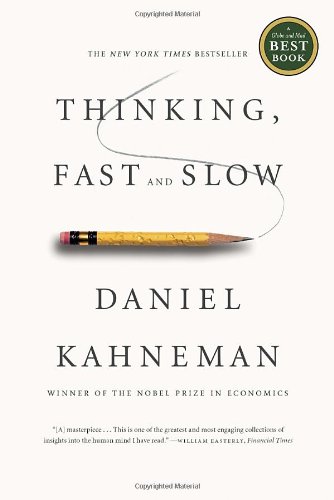

It took me ages to finish reading Thinking Fast and Slow. I must have stopped to reflect about 50 times. The book is about judgment and decision-making, and was written by a psychologist. While I was already familiar with many of the theories – Daniel Kahneman has been working since the early 1970s – it was edifying to have them explained in one text.

Because it took me so long to read, I had a whack of life experiences while reading, and lots of time to consider my own actions or inactions.

It was brutal.

The book is about how we think, and about frequent errors in judgment. As Kahneman explains it, we have two modes of thinking: one fast, one slow. Basically, we are lazy so we think fast a lot. Fast thinking is emotional, stereotypic, and subconscious. (This isn’t conjecture: Kahneman backs up all of his statements with studies.)

Slow thinking is effortful, infrequent, and conscious.

It is exhausting to think slow:

“The often-used phrase ‘pay attention’ is apt: you dispose of a limited budget of attention that you can allocate to activities, and if you try to go beyond your budget, you will fail. It is the mark of effortful activities that they interfere with each other, which is why it is difficult or impossible to conduct several at once. You could not compute the product of 17 X 24 while making a left turn into dense traffic, and you certainly should not try. You can do several things at once, but only if they are easy and undemanding.”

Because we tend to think fast most of the time, and slow only when we have to, we are prone to making logical mistakes. Kahneman demonstrates that: “People who are cognitively busy are also more likely to make selfish choices, use sexist language, and make superficial judgment in social situations.”

Which means, basically, we’re all a lot more selfish, sexist, and superficial than we think.

During a dark period in my life, I used a lot of (very common) cognitive distortions. I took things personally, I used emotional reasoning, I thought in polarized terms. If someone didn’t call me back, I thought they hated me. I still struggle, to a certain extent: I catastrophize more than I should (ahem! you can even see some signs of it in this post). But training myself to not think like this – to think more rationally – has been the best thing I’ve ever done for myself.

According to the book, “We are evidently ready from birth to have impressions of causality, which do not depend on reasoning about patterns of causation.”

We see patterns where there are none. We search for threats and give certain characteristics ominous behaviours. Some believe we’ve evolved this way: you’re more likely to survive if you can sense danger. But there’s a downside:

“The perception of intention and emotion is irresistible; only people afflicted by autism do not experience it. All this is entirely in your mind, of course. Your mind is ready and even eager to identify agents, assign them personality traits and specific intentions, and view their actions as expressing individual propensities.”

This reminded me so much of my dark-thought period. How many times have you thought that someone who frowns a lot was mean? Or someone who smiles a lot is nice? “People are prone to apply causal thinking inappropriately, to situations that require statistical reasoning.”

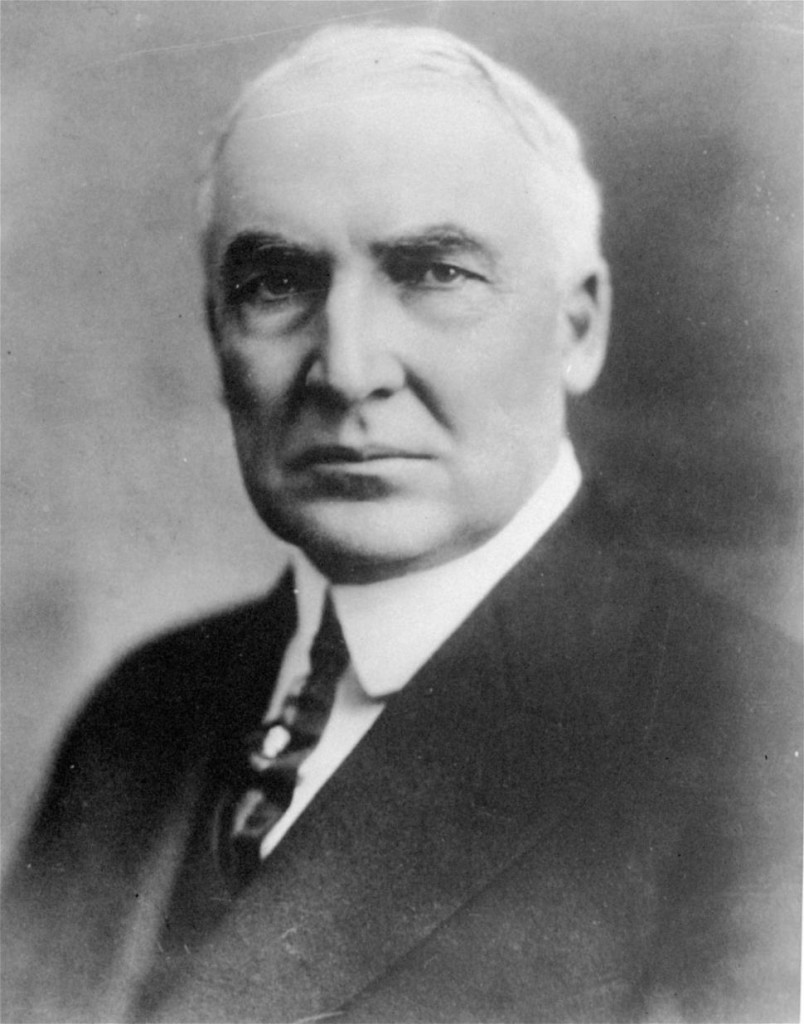

I read once that Warren Harding, now thought of as being one of the worst Presidents in the history of the United States, a man historians now describe as “woefully under-qualified for the job”, was chosen to be the presidential candidate because “he looked like a President“.

Of course, this works the opposite way too. Yesterday, on my walk to work, I saw a man who was dressed a certain way. I thought: “he is having a HARD TIME” – his shoes were squeaky, his clothes didn’t fit, they were worn and mis-matched – and then I caught myself – just because he looked like he’d fallen on hard times, it didn’t mean he had.

These are examples of thinking fast, and making an error in judgment. Kahneman describes this particular error as a “halo effect”: “If you like the president’s politics, you probably like his voice and his appearance as well. The tendency to like (or dislike) everything about a person – including things you have not observed – is known as the halo effect.”

He later defends the action of stereotyping – it’s a quick way to process information – but it also means you may be inaccurate.

I thought a lot about how I play with impressions: how I dress at work versus how I dress on weekends. How I try to make people think I look either more or less capable than I am – either consciously or subconsciously. Even here, writing this: if I use a phrase like “cognitive distortion”, will you think I’m more/less intelligent than I actually am? (Say “more”! “More”!)

You can see why reading the book took AGES!

He explains other fallacies too, and all were fascinating.

I think differently now about pricing, about crime sentencing, about job interviews, about negotiating. Reading this while watching Making a Murderer was a trip: there are so many assumptions that go into building a court case.

It wasn’t an easy read, especially if any part of you is at all introspective, but I’d highly recommend it. Particularly if you, like most humans, are prone to making errors in judgment.

You can read another review of the book here.